Checkout

Top Celebrities

- 50 Cent

- Aaron Carter

- Abigail Clancy

- Academy Awards

- Adam Lambert

- Adam Sandler

- Adnan Ghalib

- Adrian Grenier

- Adriana Lima

- Adrianne Curry

- Adrienne Bailon

- Aida Yespica

- Aisha Tyler

- Aisleyne Horgan-Wallace

- Akon

- Al Gore

- Alaina Alexander

- Alana Curry

- Alec Baldwin

- Aleksandra Jordan

- Alena Seredova

- Alessandra Ambrosio

- Alessia Ventura

- Alex Grace

- Alex Rodriguez

- Ali Larter

- Ali Lohan

- Alicia Keys

- Alina Vacariu

- Allegra Versace

- Alley Bagget

- Alyssa Milano

- Amanda Bynes

- Amanda Harrington

- Amanda Peet

- America Ferrera

- American Idol

- Amy Polumbo

- Amy Winehouse

- Ana Beatriz Barros

- Ana Kournikova

- Anahi Gonzalez

- Andy Dick

- Andy Garcia

- Ang Lee

- Angelina Jolie

- Angie Harmon

- Anna Faris

- Anna Friel

- Anna Kournikova

- Anna Lynne McCord

- Anna Nicole Smith

- Anna Paquin

- Annalynne McCord

- Anne Hathaway

- Anne Heche

- Anthony Hopkins

- Antonella Barba

- Antonio Banderas

- April Scott

- Arnold Schwarzenegger

- Aruna Shields

- Ashanti

- Ashlee Simpson

- Ashley Dupre

- Ashley Greene

- Ashley Olsen

- Ashley Tisdale

- Ashton Kutcher

- Aubrey O'Day

- Audrina Patridge

- Austin Green

- Avril Lavigne

- Bai Ling

- Bam Margera

- Bar Refaeli

- Barack Obama

- Barbra Streisand

- Barron Hilton

- Ben Affleck

- Ben Stein

- Ben Stiller

- Bernie Mac

- Beyonce

- Beyonce Knowles

- Bikini Pictures

- Bill O'Reilly

- Bjork

- Blake Lively

- Bobby Brown

- Bono

- Borat

- Brad Pitt

- Brandon Davis

- Brenda Song

- Bridget Marquardt

- Britney Spears

- Brittany Murphy

- Brittany Snow

- Brody Jenner

- Brook Shields

- Brooke Burke

- Brooke Burns

- Brooke Hogan

- Brooke Shields

- Bruce Willis

- Cameron Diaz

- Camilla Belle

- Candice Michelle

- Caprice Bourett

- Caption Me

- Carmen Electra

- Carrie Prejean

- Carrie Underwood

- Cassie

- Cate Blanchett

- Catherine Zeta-Jones

- Celebrities

- Celebrity Gossip

- Celebrity Pictures

- Celine Dion

- Chad Michael Murray

- Chanelle Hayes

- Charisma Carpetner

- Charlie Sheen

- Charlize Theron

- Cheryl Cole

- Cheryl Tweedy

- Chris Benoit

- Chris Brown

- Chris Tarrant

- Christian Bale

- Christie Binkley

- Christina Aguiera

- Christina Aguilera

- Christina Applegate

- Christina Milian

- Christina Ricci

- Christoper Masterson

- Christopher Walken

- Chuck Nice

- Ciara

- Cindy Crawford

- Cindy Margolis

- Cindy Taylor

- Claudia Schiffer

- Clay Aiken

- Clive Owen

- Coco

- Cory Lidle

- Courteney Cox

- Courtney Cox

- Courtney Love

- Criss Angel

- Cristiano Ronaldo

- Cyndi Lauper

- Dakota Fanning

- Dane Cook

- Dania Ramirez

- Daniel Craig

- Daniel Radcliffe

- Daniel Smith

- Danielle Lloyd

- Danity Kane

- Dannii Minogue

- Danny Boyle

- Dave Navarro

- David Beckham

- David Blaine

- David Faustino

- David Hasselhoff

- David Letterman

- David Spade

- Dean McDermott

- Dean Sheremet

- Debbie Rowe

- Delta Goodrem

- Denise Milani

- Denise Richards

- Dennis Leary

- Diddy

- Dina Lohan

- Diora Baird

- Dita Von Teese

- DJ AM

- DMX

- Don Cheadle

- Don Imus

- Donal Logue

- Donald Trump

- Doug Reinhardt

- Dr Dre

- Drew Barrymore

- Dustin Diamond

- Eddie Murphy

- Edward Norton

- Elin Woods

- Elisha Cuthbert

- Eliza Dushku

- Elizabeth Hurley

- Elle Macpherson

- Ellen Pompeo

- Elton John

- Elyse Umemoto

- Emily Blun

- Emily Osment

- Emily Scott

- Eminem

- Emma B

- Emma Roberts

- Emma Watson

- Emmanuelle Chriqui

- Emmy Rosum

- Erich Schultz

- Erin Wasson

- Eva Green

- Eva Longoria

- Eva Mendes

- Evangeline Lilly

- Fabiana Tambosi

- Farrah Fawcett

- Fat Joe

- Fergie

- Fernanda Tavares

- Flavor of Love

- Foxy Brown

- Freida Pinto

- Gavin Rossdale

- Gemma Atkinson

- George Carlin

- George Clooney

- George Michael

- Gilles Marini

- Gisele Bundchen

- Good Charlotte

- Grey's Anatom

- Guy Ritchie

- Gwen Stefani

- Gwyneth Paltrow

- Hail Gossip Blogs

- Hails Hottie Picks

- Hails Recap

- Haired Pea

- Halle Berry

- Harrison Ford

- Harry Morton

- Harry Potter

- Hayden Panettiere

- Haylie Duff

- Heath Ledger

- Heather Graham

- Heather Locklear

- Heather Mills

- Heidi Klum

- Heidi Montag

- Helena Christensen

- Hilary Duff

- Hilary Swank

- Hillary Clinton

- Holly Madison

- Holly Valance

- Hot Girls

- Hot kiss scene

- Howard K. Stern

- Howard Stern

- Hugh Grant

- Hugh Hefner

- Hugh Jackman

- Hulk Hogan

- Ice Cube

- Iphone

- Irina Shaykhilsamova

- Isaac Cohen

- Isaac Hayes

- Isabel Fontana

- Isaiah Washington

- Ivanka Trump

- Izabel Goulart

- Jack Bauer

- Jack Black

- Jack Nicholson

- Jackie Chan

- Jade

- Jaime Pressly

- Jake Gyllenhaal

- Jakki Degg

- James Blunt

- James Bond

- Jami Miller

- Jamie Foxx

- Jamie Hince

- Jamie Lynn Spears

- Jamie Oliver

- Jamie Pressly

- Jamie-Lynn Sigler

- Jane Fonda

- Jane Olson

- Janet Jackson

- Jaslene Gonzalez

- Jason Filyaw

- Jason Lee

- Jason Lewis

- Jason Mesnick

- Jay-Z

- Jayden

- Jayden James

- Jeff Goldblum

- Jenna Fischer

- Jenna Jameson

- Jennie Garth

- Jennifer Aniston

- Jennifer Ellison

- Jennifer Garner

- Jennifer Hawkins

- Jennifer Hudson

- Jennifer Lopez

- Jennifer Love Hewitt

- Jennifer Morrison

- Jennifer Walcott

- Jenny Frost

- Jenny McCarthy

- Jeremy Piven

- Jermaine Dupri

- Jerry Seinfeld

- Jessica Alba

- Jessica Biel

- Jessica Lowndes

- Jessica Simpson

- Jessica White

- Jessie Jane

- Jewel

- Jim Carey

- Jim Carrey

- Jimmy Fallon

- Joan Rivers

- Joanna Krupa

- Joaquin Phoenix

- Jodie Marsh

- Jodie Sweetin

- Joe Francis

- Joe Jackson

- Joe Simpson

- Joel Madden

- John Cusack

- John Lennon

- John Mayer

- John Ritter

- John Stewart

- John Travolta

- Johnny Depp

- Johnny Fairplay

- Johnson Rocks

- Jojo

- Jolene Blalock

- Jon Gosselin

- Jon Lovitz

- Jonas Brothers

- Jonathan Rhys Meyers

- Jordan

- Jordan Bratman

- Jorge Nunez

- Josh Duhamel

- Josh Hartnett

- Josie Maran

- Joss Stone

- Jude Law

- Julia Roberts

- Julia Stiles

- Julianne Hough

- Juliette Lewis

- Justin Bieber

- Justin Gaston

- Justin Timberlake

- Juveline

- Kaiane Aldorino

- Kaley Cuoco

- Kanye West

- Kardashian

- Kari Ann Peniche

- Karina Smirnoff

- Karolina Kurkova

- Kate Beckinsale

- Kate Bosworth

- Kate Gosselin

- Kate Hudson

- Kate Moss

- Kate Winslet

- Katharine Mcphee

- Katherine Heigl

- Katherine McPhee

- Kathy Hilton

- Katie Downes

- Katie Holmes

- Katie Lohmann

- Katie Price

- Katie Rees

- Katy Perry

- Ke$ha

- Keanu Reeves

- Keeley Hazell

- Keira Knightley

- Keisha Buchanan

- Keith Richards

- Keith Urban

- Kelly Bensimon

- Kelly Brook

- Kelly Clarkson

- Kelly Osbourne

- Kelly Pickler

- Kelly Ripa

- Kelly Rutherford

- Kendra Jade

- Kendra Wilkinson

- Keri Russell

- Kerri Kasem

- Kevin Costner

- Kevin Federline

- Khloe Kardashian

- Kiefer Sutherland

- Kim Kardashian

- Kimberly Stewart

- Kimora Lee Simmons

- Kingston

- Kirsten Dunst

- Kobe Bryant

- Kourtney Kardashian

- Kristanna Loken

- Kristen Bell

- Kristen Dalton

- Kristen Stewart

- Kristin Cavallari

- Kristin Davis

- Kristy Swanson

- Kurt Cobain

- Kylie Minogue

- L.L. Cool J

- Lacey Chabert

- Lady GaGa

- Lance Bass

- Larry Birkhead

- Larry King

- Larry Rudolph

- Laura Prepon

- Lauren Conrad

- Lauren Hutton

- Lauren Nelson

- Laurence Fishburne

- Leann Rimes

- Lee Ann Rimes

- Leelee Sobieski

- Leighton Meester

- Leo DiCaprio

- Leona Lewis

- Leonardo DiCaprio

- Leticia Cline

- Lil Wayne

- Lilly Allen

- Lily Allen

- Lindsay Lohan

- Lindsey Vonn

- Lionel Richie

- Lisa Gleave

- Lisa Loeb

- Lisa Marie Scott

- Lisa Ray

- Lisa Rhinna

- Lisa Snowdon

- Liv Tyler

- Lori Loughlin

- Louise Redknapp

- Lucie Silvas

- Lucy Liu

- Lucy Pinder

- Luke Wilson

- Maddox

- Madonna

- Maggie Gyllenhaal

- Mandy Moore

- Marcia Cross

- Maria Menounos

- Maria Sergeyeva

- Mariah Carey

- Mario Lopez

- Marisa Miller

- Marisa Tomei

- Mark Wahlberg

- Mary J. Blige

- Mary-Kate Olsen

- Mary-Louise Parker

- Maryse Ouellet

- Matt Damon

- Matt Lauer

- Matthew McConaughey

- Matthew Perry

- May Andersen

- McShane

- Meg Ryan

- Meg White

- Megan Fox

- Meghan McCain

- Mel Gibson

- Melania Knauss

- Melanie Brown

- Mena Suvari

- Michael Douglas

- Michael Jackson

- Michael Moore

- Michelle Marsh

- Michelle McCool

- Michelle Obama

- Michelle Rodriguez

- Michelle Trachtenberg

- Michelle Williams

- Mick Jagger

- Mike Tyson

- Mila Kunis

- Miley Cyrus

- Milo Ventimiglia

- Minka Kelly

- Miranda Kerr

- Mischa Barton

- Miss Nevada

- Miss Universe 2010

- Moby

- Monica Bellucci

- Morgan Freeman

- Movies

- Myleene Klass

- Nadine Velasquez

- Nadya Suleman

- Naomi Campbe

- Naomi Watts

- Nas

- Natalie Maines

- Natalie Portman

- Natasha Bedingfield

- Natasha Henstridge

- Natasha Richardson

- Neha Dhupia

- new gossips

- new movie

- New York Yankees

- Nick Carter

- Nick Jonas

- Nick Lachey

- Nicky Hilton

- Nicolas Cage

- Nicole Eggert

- Nicole Kidman

- Nicole Richie

- Nicole Scherzinger

- Nicolette Sheridan

- Nikki Ziering

- Nipple Slip

- Notorious B.I.G.

- Octomom

- Odette Yustman

- OJ Simpson

- Olga Kurylenko

- olivi

- Olivia Mojica

- Olivia Munn

- Olivia Newton John

- Olivia Wilde

- Oprah

- Orlando Bloom

- Orlando Brown

- Oscar de la Hoya

- Oscars

- Owen Wilson

- Pamela Anderson

- Paris Hilton

- Patricia Arquette

- Patrick Dempsey

- Patrick McDermott

- Patrick Swayze

- Paul Oakenfold

- Paul Rudd

- Paul Walker

- Paula Abdul

- Penelope Cruz

- Perez Hilton

- Pete Doherty

- Pete Wentz

- Peter Andre

- Peter Facinelli

- Peter Greene

- Petra Nemcova

- Phil Collins

- Phoebe Price

- Pink

- Piper Perabo

- Polls

- Primetime Emmys

- Prince Harry

- Princess Beatrice

- Queen Elizabeth

- Queen Latifah

- R. Kelly

- Rachael Ray

- Rachel Bilson

- Rachel Hunter

- Rachel Stevens

- Rachel Uchitel

- Rachelle Lefevre

- Randy Quaid

- Ray J

- Reese Witherspoon

- Renee Olstead

- Renee Zellweger

- Richard Lugner

- Richie Sambora

- Ricky Gervais

- Rihanna

- Rima Fakih

- Rob Schneider

- Robbie Williams

- Robert Pattinson

- Ron Jeremy

- Rosario Dawson

- Rosie Huntington

- Rosie Odonnell

- Roxanne Pallet

- Rumer Willis

- Russell Brand

- Russell Crowe

- Ryan Phillippe

- Ryan Seacres

- Sacha Baron Cohen

- Sadie Frost

- Salma Hayek

- Samantha Ronson

- Samia Smith

- Samuel L. Jackson

- Sandee Westgate

- Sandra Bullock

- Sanjaya

- Sara Foster

- Sarah Harding

- Sarah Jessica Parker

- Sarah Michelle Gellar

- Sarah Shahi

- Sarah Silverman

- Scarlett Johansson

- Scientology

- Sean Penn

- Sean Preston

- Selena Gomez

- Selita Ebanks

- Selma Blair

- sex tape

- Shakira

- Shana Prevette

- Shanna Moakler

- Shaquille O'Neal

- Sharon Stone

- Shauna Sands

- Shawn Johnson

- Shenae Grimes

- Sheryl Crow

- Shia LaBeouf

- Shiloh Nouvel Pitt

- Shyamali Malakar

- Sienna Miller

- Simon Cowell

- Sin City

- Sofia Vergara

- Sonam Kapoor

- Sophie Monk

- South Park

- Stacy Dash

- Stacy Keibler

- Star Jones

- Stavros Niarchos

- Steve Irwin

- Steve O

- Steven Spielberg

- Suge Knight

- Sunny Leone

- Suri Cruise

- Susan Boyle

- Sutton Pierce Federline

- Sylvester Stallone

- T.I.

- Tailor Made

- Tania Zaetta

- Tara Conner

- Tara Elizabeth Conner

- Tara Elizabeth Connor

- Tara Reid

- Tatu

- Taylor Lautner

- Taylor Momsen

- Taylor Swift

- Team Bill

- Ted Hughes

- Tera Patrick

- Teresa Palmer

- Teri Harrison

- Teri Hatcher

- The Dark Knight

- The Game

- The Morning Quicky

- Tiffany Taylor

- Tiger Woods

- Tila Tequila

- Tobey Maguire

- Tom Arnold

- Tom Brady

- Tom Cruise

- Tom Hanks

- Tommy Lee Jones

- Tony parker

- Tori Spelling

- Travis Barker

- Tricia Helfer

- Tyler Perry

- Tyra Banks

- Uffie

- Uma Thurman

- Usher

- Vanessa Hudgens

- Vanessa Marcil

- Vanessa Minnillo

- Victoria Beckham

- Victoria Justice

- Victoria Silvstedt

- Vida Guerra

- Vin Diesel

- Vince Vaughn

- Virginia Tech

- Website News

- Weird Al

- Wesley Snipes

- Whitney Houston

- whitney Port

- Whoopi Goldberg

- Will Ferrell

- Willem Defoe

- Wilmer Valderrama

- Winona Ryder

- Woody Harrelson

- Woody Harrison

- Yesica Toscanni

- YouTube

- Yukie Kawamura

- Zac Efron

- Zachery Ty Bryan

- Zooey Deschane

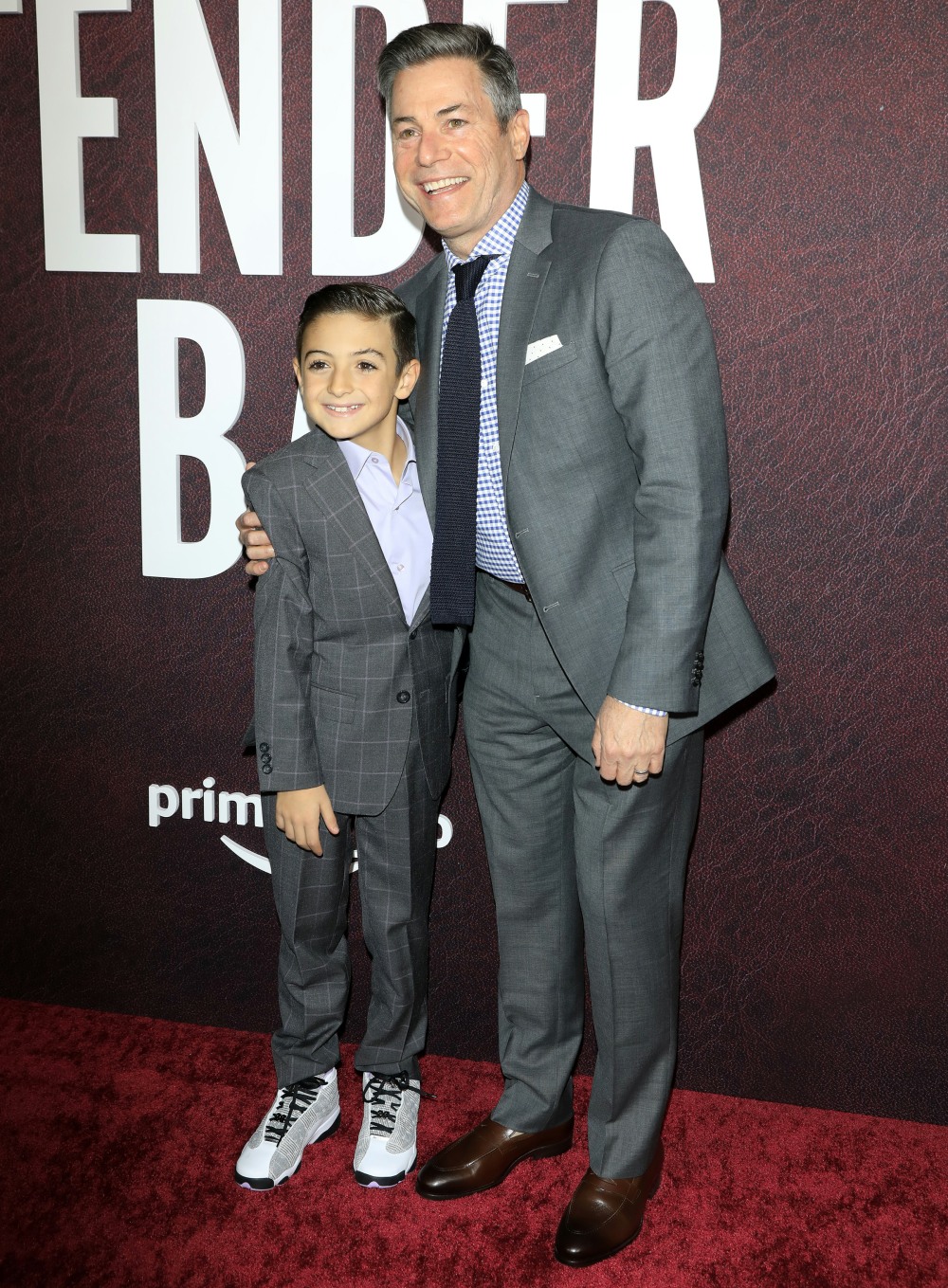

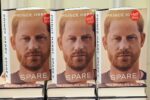

JR Moehringer reveals what it was like to ghostwrite for Prince Harry on ‘Spare’

Author: | Filed under: CelebritiesJ. R. Moehringer was Prince Harry’s ghostwriter for Spare. Before now, we never heard from Moehringer about what it was like to work with Harry, how collaborative the process was or whether Moehringer acted more as an editor or a co-writer. Now we know, thanks to this wonderful piece Moehringer wrote for the New Yorker, “Notes from Prince Harry’s Ghostwriter.” The piece starts out with Moehringer explaining a 2022 argument he had with Harry over Zoom about one passage in the book, about Harry’s military training, and Harry fighting to include his own snappy comeback to the line-crossing moment when his “interrogators” brought up his mother. They went back and forth about one line, both men growing furious and exasperated with each other until the moment when Moehringer was sure Harry was about to fire him. Then Harry accepted JR’s call and said “I really enjoy getting you worked up like that.” Here are some highlights from the piece:

This is amazing: The ghostwriter for Julian Assange wrote twenty-five thousand words about his methodology, and it sounded to me like Elon Musk on mushrooms—on Mars. That same ghost, however, published a review of “Spare” describing Harry as “off his royal tits” and me as going “all Sartre or Faulkner,” so what do I know? Who am I to offer rules? Maybe the alchemy of each ghost-author pairing is unique.

How he got the gig: Then, in the summer of 2020, I got a text. The familiar query. Would you be interested in speaking with someone about ghosting a memoir? I shook my head no. I covered my eyes. I picked up the phone and heard myself blurting, Who? Prince Harry. I agreed to a Zoom. I was curious, of course. Who wouldn’t be? I wondered what the real story was. I wondered if we’d have any chemistry. We did, and there was, I think, a surprising reason. Princess Diana had died twenty-three years before our first conversation, and my mother, Dorothy Moehringer, had just died, and our griefs felt equally fresh.

What enticed him about ghosting for Harry: Harry had no deadline, however, and that enticed me. Many authors are in a hot hurry, and some ghosts are happy to oblige. They churn and burn, producing three or four books a year. I go painfully slow; I don’t know any other way. Also, I just liked the dude. I called him dude right away; it made him chuckle. I found his story, as he outlined it in broad strokes, relatable and infuriating. The way he’d been treated, by both strangers and intimates, was grotesque.

Ghosting in privacy: Harry and I made steady progress in the course of 2020, largely because the world didn’t know what we were up to. We could revel in the privacy of our Zoom bubble. As Harry grew to trust me, he brought other people into the bubble, connecting me with his inner circle, a vital phase in every ghosting job. There is always someone who knows your author’s life better than he does, and your task is to find that person fast and interview his socks off.

His first travels to Montecito: As the pandemic waned, I was finally able to travel to Montecito. I went once with my wife and children. (Harry won the heart of my daughter, Gracie, with his vast “Moana” scholarship; his favorite scene, he told her, is when Heihei, the silly chicken, finds himself lost at sea.) I also went twice by myself. Harry put me up in his guesthouse, where Meghan and Archie would visit me on their afternoon walks. Meghan, knowing I was missing my family, was forever bringing trays of food and sweets.

Harry’s candor: In due time, no subject was off the table. I felt honored by his candor, and I could tell that he felt astonished by it. And energized. While I always emphasized storytelling and scenes, Harry couldn’t escape the wish that “Spare” might be a rebuttal to every lie ever published about him. As Borges dreamed of endless libraries, Harry dreams of endless retractions, which meant no end of revelations. He knew, of course, that some people would be aghast at first. “Why on earth would Harry talk about that?” But he had faith that they would soon see: because someone else already talked about it, and got it wrong.

Then someone leaked the news of the book: Whoever it was, their callousness toward Harry extended to me. I had a clause in my contract giving me the right to remain unidentified, a clause I always insist on, but the leaker blew that up by divulging my name to the press. Along with pretty much anyone who has had anything to do with Harry, I woke one morning to find myself squinting into a gigantic searchlight. Every hour, another piece would drop, each one wrong. My fee was wrong, my bio was wrong, even my name. One royal expert cautioned that, because of my involvement in the book, Harry’s father should be “looking for a pile of coats to hide under.” When I mentioned this to Harry, he stared. “Why?” “Because I have daddy issues.” We laughed and got back to discussing our mothers.

The British media’s unhinged reaction to Spare: When the book was officially released, the bad translations didn’t stop. They multiplied. The British press now converted the book into their native tongue, that jabberwocky of bonkers hot takes and classist snark. Facts were wrenched out of context, complex emotions were reduced to cartoonish idiocy, innocent passages were hyped into outrages—and there were so many falsehoods. One British newspaper chased down Harry’s flight instructor. Headline: “Prince Harry’s army instructor says story in Spare book is ‘complete fantasy.’ ” Hours later, the instructor posted a lengthy comment beneath the article, swearing that those words, “complete fantasy,” never came out of his mouth. Indeed, they were nowhere in the piece, only in the bogus headline, which had gone viral. The newspaper had made it up, the instructor said, stressing that Harry was one of his finest students.

Spare is rigorously fact-checked: Within days, the amorphous campaign against “Spare” seemed to narrow to a single point of attack: that Harry’s memoir, rigorously fact-checked, was rife with errors. I can’t think of anything that rankles quite like being called sloppy by people who routinely trample facts in pursuit of their royal prey, and this now happened every few minutes to Harry and, by extension, to me.

The TK Maxx thing: In one section of the book, for instance, Harry reveals that he used to live for the yearly sales at TK Maxx, the discount clothing chain. Not so fast, said the monarchists at TK Maxx corporate, who rushed out a statement declaring that TK Maxx never has sales, just great savings all the time! Oh, snap! Gotcha, Prince George Santos! Except that people around the world immediately posted screenshots of TK Maxx touting sales on its official Twitter account. (Surely TK Maxx’s effort to discredit Harry’s memoir was unrelated to the company’s long-standing partnership with Prince Charles and his charitable trust.)

Stalked by British reporters & paparazzi: Days earlier, we’d been stalked, followed in our car as we drove our son to preschool. When I lifted him out of his seat, a paparazzo leaped from his car and stood in the middle of the road, taking aim with his enormous lens and scaring the hell out of everyone at dropoff. Then, not one hour later, as I sat at my desk, trying to calm myself, I looked up to see a woman’s face at my window. As if in a dream, I walked to the window and asked, “Who are you?” Through the glass, she whispered, “I’m from the Mail on Sunday.”… I called [Harry]… Harry was all heart. He asked if my family was O.K., asked for physical descriptions of the people harassing us, promised to make some calls, see if anything could be done. We both knew nothing could be done, but still. I felt gratitude, and some regret. I’d worked hard to understand the ordeals of Harry Windsor, and now I saw that I understood nothing. Empathy is thin gruel compared with the marrow of experience. One morning of what Harry had endured since birth made me desperate to take another crack at the pages in “Spare” that talk about the media.

Harry was happy that people were reading the book: He appeared, marching toward us, looking flushed. Uh-oh, I thought, before registering that it was a good flush. His smile was wide as he embraced us both. He was overjoyed by many things. The numbers, naturally. Guinness World Records had just certified his memoir as the fastest-selling nonfiction book in the history of the world. But, more than that, readers were reading, at last, the actual book, not Murdoched chunks laced with poison, and their online reviews were overwhelmingly effusive. Many said Harry’s candor about family dysfunction, about losing a parent, had given them solace.

The book party: There were several lovely toasts to Harry, then the Prince stepped forward. I’d never seen him so self-possessed and expansive. He thanked his publishing team, his editor, me. He mentioned my advice, to “trust the book,” and said he was glad that he did, because it felt incredible to have the truth out there, to feel—his voice caught—“free.” There were tears in his eyes. Mine, too.”

Freedom: “I couldn’t help obsessing about that word “free.” If he’d used that in one of our Zoom sessions, I’d have pushed back. Harry first felt liberated when he fell in love with Meghan, and again when they fled Britain, and what he felt now, for the first time in his life, was heard. That imperious Windsor motto, “Never complain, never explain,” is really just a prettified omertà, which my wife suggests might have prolonged Harry’s grief. His family actively discourages talking, a stoicism for which they’re widely lauded, but if you don’t speak your emotions you serve them, and if you don’t tell your story you lose it—or, what might be worse, you get lost inside it. Telling is how we cement details, preserve continuity, stay sane. We say ourselves into being every day, or else. Heard, Harry, heard—I could hear myself making the case to him late at night, and I could see Harry’s nose wrinkle as he argued for his word, and I reproached myself once more: Not your effing book.

Meghan is so thoughtful: “But, after we hugged Harry goodbye, after we thanked Meghan for toys she’d sent our children, I had a second thought about silence. Ghosts don’t speak—says who? Maybe they can. Maybe sometimes they should.

You can tell how much Moehringer likes Harry, but even more than that, he respects Harry and the ordeal Harry has been through since birth, through the “contract” with the British media, a contract which has calcified to a global hate campaign against the redhead who escaped to America. I would love to know all of the people in Harry’s life who spoke to JR and who he found the most helpful. I would imagine a few former palace employees were among them. While Moehringer doesn’t say this explicitly (he doesn’t have to), he’s also describing how Meghan didn’t have the first thing to do with the book, unlike all of those reports from the British media. This was Harry and JR, toiling away via Zoom and in person, constantly editing and rewriting and figuring out which parts to include. Anyway, I hope JR and Harry are working on a second book!

Leave a reply