Checkout

Top Celebrities

- 50 Cent

- Aaron Carter

- Abigail Clancy

- Academy Awards

- Adam Lambert

- Adam Sandler

- Adnan Ghalib

- Adrian Grenier

- Adriana Lima

- Adrianne Curry

- Adrienne Bailon

- Aida Yespica

- Aisha Tyler

- Aisleyne Horgan-Wallace

- Akon

- Al Gore

- Alaina Alexander

- Alana Curry

- Alec Baldwin

- Aleksandra Jordan

- Alena Seredova

- Alessandra Ambrosio

- Alessia Ventura

- Alex Grace

- Alex Rodriguez

- Ali Larter

- Ali Lohan

- Alicia Keys

- Alina Vacariu

- Allegra Versace

- Alley Bagget

- Alyssa Milano

- Amanda Bynes

- Amanda Harrington

- Amanda Peet

- America Ferrera

- American Idol

- Amy Polumbo

- Amy Winehouse

- Ana Beatriz Barros

- Ana Kournikova

- Anahi Gonzalez

- Andy Dick

- Andy Garcia

- Ang Lee

- Angelina Jolie

- Angie Harmon

- Anna Faris

- Anna Friel

- Anna Kournikova

- Anna Lynne McCord

- Anna Nicole Smith

- Anna Paquin

- Annalynne McCord

- Anne Hathaway

- Anne Heche

- Anthony Hopkins

- Antonella Barba

- Antonio Banderas

- April Scott

- Arnold Schwarzenegger

- Aruna Shields

- Ashanti

- Ashlee Simpson

- Ashley Dupre

- Ashley Greene

- Ashley Olsen

- Ashley Tisdale

- Ashton Kutcher

- Aubrey O'Day

- Audrina Patridge

- Austin Green

- Avril Lavigne

- Bai Ling

- Bam Margera

- Bar Refaeli

- Barack Obama

- Barbra Streisand

- Barron Hilton

- Ben Affleck

- Ben Stein

- Ben Stiller

- Bernie Mac

- Beyonce

- Beyonce Knowles

- Bikini Pictures

- Bill O'Reilly

- Bjork

- Blake Lively

- Bobby Brown

- Bono

- Borat

- Brad Pitt

- Brandon Davis

- Brenda Song

- Bridget Marquardt

- Britney Spears

- Brittany Murphy

- Brittany Snow

- Brody Jenner

- Brook Shields

- Brooke Burke

- Brooke Burns

- Brooke Hogan

- Brooke Shields

- Bruce Willis

- Cameron Diaz

- Camilla Belle

- Candice Michelle

- Caprice Bourett

- Caption Me

- Carmen Electra

- Carrie Prejean

- Carrie Underwood

- Cassie

- Cate Blanchett

- Catherine Zeta-Jones

- Celebrities

- Celebrity Gossip

- Celebrity Pictures

- Celine Dion

- Chad Michael Murray

- Chanelle Hayes

- Charisma Carpetner

- Charlie Sheen

- Charlize Theron

- Cheryl Cole

- Cheryl Tweedy

- Chris Benoit

- Chris Brown

- Chris Tarrant

- Christian Bale

- Christie Binkley

- Christina Aguiera

- Christina Aguilera

- Christina Applegate

- Christina Milian

- Christina Ricci

- Christoper Masterson

- Christopher Walken

- Chuck Nice

- Ciara

- Cindy Crawford

- Cindy Margolis

- Cindy Taylor

- Claudia Schiffer

- Clay Aiken

- Clive Owen

- Coco

- Cory Lidle

- Courteney Cox

- Courtney Cox

- Courtney Love

- Criss Angel

- Cristiano Ronaldo

- Cyndi Lauper

- Dakota Fanning

- Dane Cook

- Dania Ramirez

- Daniel Craig

- Daniel Radcliffe

- Daniel Smith

- Danielle Lloyd

- Danity Kane

- Dannii Minogue

- Danny Boyle

- Dave Navarro

- David Beckham

- David Blaine

- David Faustino

- David Hasselhoff

- David Letterman

- David Spade

- Dean McDermott

- Dean Sheremet

- Debbie Rowe

- Delta Goodrem

- Denise Milani

- Denise Richards

- Dennis Leary

- Diddy

- Dina Lohan

- Diora Baird

- Dita Von Teese

- DJ AM

- DMX

- Don Cheadle

- Don Imus

- Donal Logue

- Donald Trump

- Doug Reinhardt

- Dr Dre

- Drew Barrymore

- Dustin Diamond

- Eddie Murphy

- Edward Norton

- Elin Woods

- Elisha Cuthbert

- Eliza Dushku

- Elizabeth Hurley

- Elle Macpherson

- Ellen Pompeo

- Elton John

- Elyse Umemoto

- Emily Blun

- Emily Osment

- Emily Scott

- Eminem

- Emma B

- Emma Roberts

- Emma Watson

- Emmanuelle Chriqui

- Emmy Rosum

- Erich Schultz

- Erin Wasson

- Eva Green

- Eva Longoria

- Eva Mendes

- Evangeline Lilly

- Fabiana Tambosi

- Farrah Fawcett

- Fat Joe

- Fergie

- Fernanda Tavares

- Flavor of Love

- Foxy Brown

- Freida Pinto

- Gavin Rossdale

- Gemma Atkinson

- George Carlin

- George Clooney

- George Michael

- Gilles Marini

- Gisele Bundchen

- Good Charlotte

- Grey's Anatom

- Guy Ritchie

- Gwen Stefani

- Gwyneth Paltrow

- Hail Gossip Blogs

- Hails Hottie Picks

- Hails Recap

- Haired Pea

- Halle Berry

- Harrison Ford

- Harry Morton

- Harry Potter

- Hayden Panettiere

- Haylie Duff

- Heath Ledger

- Heather Graham

- Heather Locklear

- Heather Mills

- Heidi Klum

- Heidi Montag

- Helena Christensen

- Hilary Duff

- Hilary Swank

- Hillary Clinton

- Holly Madison

- Holly Valance

- Hot Girls

- Hot kiss scene

- Howard K. Stern

- Howard Stern

- Hugh Grant

- Hugh Hefner

- Hugh Jackman

- Hulk Hogan

- Ice Cube

- Iphone

- Irina Shaykhilsamova

- Isaac Cohen

- Isaac Hayes

- Isabel Fontana

- Isaiah Washington

- Ivanka Trump

- Izabel Goulart

- Jack Bauer

- Jack Black

- Jack Nicholson

- Jackie Chan

- Jade

- Jaime Pressly

- Jake Gyllenhaal

- Jakki Degg

- James Blunt

- James Bond

- Jami Miller

- Jamie Foxx

- Jamie Hince

- Jamie Lynn Spears

- Jamie Oliver

- Jamie Pressly

- Jamie-Lynn Sigler

- Jane Fonda

- Jane Olson

- Janet Jackson

- Jaslene Gonzalez

- Jason Filyaw

- Jason Lee

- Jason Lewis

- Jason Mesnick

- Jay-Z

- Jayden

- Jayden James

- Jeff Goldblum

- Jenna Fischer

- Jenna Jameson

- Jennie Garth

- Jennifer Aniston

- Jennifer Ellison

- Jennifer Garner

- Jennifer Hawkins

- Jennifer Hudson

- Jennifer Lopez

- Jennifer Love Hewitt

- Jennifer Morrison

- Jennifer Walcott

- Jenny Frost

- Jenny McCarthy

- Jeremy Piven

- Jermaine Dupri

- Jerry Seinfeld

- Jessica Alba

- Jessica Biel

- Jessica Lowndes

- Jessica Simpson

- Jessica White

- Jessie Jane

- Jewel

- Jim Carey

- Jim Carrey

- Jimmy Fallon

- Joan Rivers

- Joanna Krupa

- Joaquin Phoenix

- Jodie Marsh

- Jodie Sweetin

- Joe Francis

- Joe Jackson

- Joe Simpson

- Joel Madden

- John Cusack

- John Lennon

- John Mayer

- John Ritter

- John Stewart

- John Travolta

- Johnny Depp

- Johnny Fairplay

- Johnson Rocks

- Jojo

- Jolene Blalock

- Jon Gosselin

- Jon Lovitz

- Jonas Brothers

- Jonathan Rhys Meyers

- Jordan

- Jordan Bratman

- Jorge Nunez

- Josh Duhamel

- Josh Hartnett

- Josie Maran

- Joss Stone

- Jude Law

- Julia Roberts

- Julia Stiles

- Julianne Hough

- Juliette Lewis

- Justin Bieber

- Justin Gaston

- Justin Timberlake

- Juveline

- Kaiane Aldorino

- Kaley Cuoco

- Kanye West

- Kardashian

- Kari Ann Peniche

- Karina Smirnoff

- Karolina Kurkova

- Kate Beckinsale

- Kate Bosworth

- Kate Gosselin

- Kate Hudson

- Kate Moss

- Kate Winslet

- Katharine Mcphee

- Katherine Heigl

- Katherine McPhee

- Kathy Hilton

- Katie Downes

- Katie Holmes

- Katie Lohmann

- Katie Price

- Katie Rees

- Katy Perry

- Ke$ha

- Keanu Reeves

- Keeley Hazell

- Keira Knightley

- Keisha Buchanan

- Keith Richards

- Keith Urban

- Kelly Bensimon

- Kelly Brook

- Kelly Clarkson

- Kelly Osbourne

- Kelly Pickler

- Kelly Ripa

- Kelly Rutherford

- Kendra Jade

- Kendra Wilkinson

- Keri Russell

- Kerri Kasem

- Kevin Costner

- Kevin Federline

- Khloe Kardashian

- Kiefer Sutherland

- Kim Kardashian

- Kimberly Stewart

- Kimora Lee Simmons

- Kingston

- Kirsten Dunst

- Kobe Bryant

- Kourtney Kardashian

- Kristanna Loken

- Kristen Bell

- Kristen Dalton

- Kristen Stewart

- Kristin Cavallari

- Kristin Davis

- Kristy Swanson

- Kurt Cobain

- Kylie Minogue

- L.L. Cool J

- Lacey Chabert

- Lady GaGa

- Lance Bass

- Larry Birkhead

- Larry King

- Larry Rudolph

- Laura Prepon

- Lauren Conrad

- Lauren Hutton

- Lauren Nelson

- Laurence Fishburne

- Leann Rimes

- Lee Ann Rimes

- Leelee Sobieski

- Leighton Meester

- Leo DiCaprio

- Leona Lewis

- Leonardo DiCaprio

- Leticia Cline

- Lil Wayne

- Lilly Allen

- Lily Allen

- Lindsay Lohan

- Lindsey Vonn

- Lionel Richie

- Lisa Gleave

- Lisa Loeb

- Lisa Marie Scott

- Lisa Ray

- Lisa Rhinna

- Lisa Snowdon

- Liv Tyler

- Lori Loughlin

- Louise Redknapp

- Lucie Silvas

- Lucy Liu

- Lucy Pinder

- Luke Wilson

- Maddox

- Madonna

- Maggie Gyllenhaal

- Mandy Moore

- Marcia Cross

- Maria Menounos

- Maria Sergeyeva

- Mariah Carey

- Mario Lopez

- Marisa Miller

- Marisa Tomei

- Mark Wahlberg

- Mary J. Blige

- Mary-Kate Olsen

- Mary-Louise Parker

- Maryse Ouellet

- Matt Damon

- Matt Lauer

- Matthew McConaughey

- Matthew Perry

- May Andersen

- McShane

- Meg Ryan

- Meg White

- Megan Fox

- Meghan McCain

- Mel Gibson

- Melania Knauss

- Melanie Brown

- Mena Suvari

- Michael Douglas

- Michael Jackson

- Michael Moore

- Michelle Marsh

- Michelle McCool

- Michelle Obama

- Michelle Rodriguez

- Michelle Trachtenberg

- Michelle Williams

- Mick Jagger

- Mike Tyson

- Mila Kunis

- Miley Cyrus

- Milo Ventimiglia

- Minka Kelly

- Miranda Kerr

- Mischa Barton

- Miss Nevada

- Miss Universe 2010

- Moby

- Monica Bellucci

- Morgan Freeman

- Movies

- Myleene Klass

- Nadine Velasquez

- Nadya Suleman

- Naomi Campbe

- Naomi Watts

- Nas

- Natalie Maines

- Natalie Portman

- Natasha Bedingfield

- Natasha Henstridge

- Natasha Richardson

- Neha Dhupia

- new gossips

- new movie

- New York Yankees

- Nick Carter

- Nick Jonas

- Nick Lachey

- Nicky Hilton

- Nicolas Cage

- Nicole Eggert

- Nicole Kidman

- Nicole Richie

- Nicole Scherzinger

- Nicolette Sheridan

- Nikki Ziering

- Nipple Slip

- Notorious B.I.G.

- Octomom

- Odette Yustman

- OJ Simpson

- Olga Kurylenko

- olivi

- Olivia Mojica

- Olivia Munn

- Olivia Newton John

- Olivia Wilde

- Oprah

- Orlando Bloom

- Orlando Brown

- Oscar de la Hoya

- Oscars

- Owen Wilson

- Pamela Anderson

- Paris Hilton

- Patricia Arquette

- Patrick Dempsey

- Patrick McDermott

- Patrick Swayze

- Paul Oakenfold

- Paul Rudd

- Paul Walker

- Paula Abdul

- Penelope Cruz

- Perez Hilton

- Pete Doherty

- Pete Wentz

- Peter Andre

- Peter Facinelli

- Peter Greene

- Petra Nemcova

- Phil Collins

- Phoebe Price

- Pink

- Piper Perabo

- Polls

- Primetime Emmys

- Prince Harry

- Princess Beatrice

- Queen Elizabeth

- Queen Latifah

- R. Kelly

- Rachael Ray

- Rachel Bilson

- Rachel Hunter

- Rachel Stevens

- Rachel Uchitel

- Rachelle Lefevre

- Randy Quaid

- Ray J

- Reese Witherspoon

- Renee Olstead

- Renee Zellweger

- Richard Lugner

- Richie Sambora

- Ricky Gervais

- Rihanna

- Rima Fakih

- Rob Schneider

- Robbie Williams

- Robert Pattinson

- Ron Jeremy

- Rosario Dawson

- Rosie Huntington

- Rosie Odonnell

- Roxanne Pallet

- Rumer Willis

- Russell Brand

- Russell Crowe

- Ryan Phillippe

- Ryan Seacres

- Sacha Baron Cohen

- Sadie Frost

- Salma Hayek

- Samantha Ronson

- Samia Smith

- Samuel L. Jackson

- Sandee Westgate

- Sandra Bullock

- Sanjaya

- Sara Foster

- Sarah Harding

- Sarah Jessica Parker

- Sarah Michelle Gellar

- Sarah Shahi

- Sarah Silverman

- Scarlett Johansson

- Scientology

- Sean Penn

- Sean Preston

- Selena Gomez

- Selita Ebanks

- Selma Blair

- sex tape

- Shakira

- Shana Prevette

- Shanna Moakler

- Shaquille O'Neal

- Sharon Stone

- Shauna Sands

- Shawn Johnson

- Shenae Grimes

- Sheryl Crow

- Shia LaBeouf

- Shiloh Nouvel Pitt

- Shyamali Malakar

- Sienna Miller

- Simon Cowell

- Sin City

- Sofia Vergara

- Sonam Kapoor

- Sophie Monk

- South Park

- Stacy Dash

- Stacy Keibler

- Star Jones

- Stavros Niarchos

- Steve Irwin

- Steve O

- Steven Spielberg

- Suge Knight

- Sunny Leone

- Suri Cruise

- Susan Boyle

- Sutton Pierce Federline

- Sylvester Stallone

- T.I.

- Tailor Made

- Tania Zaetta

- Tara Conner

- Tara Elizabeth Conner

- Tara Elizabeth Connor

- Tara Reid

- Tatu

- Taylor Lautner

- Taylor Momsen

- Taylor Swift

- Team Bill

- Ted Hughes

- Tera Patrick

- Teresa Palmer

- Teri Harrison

- Teri Hatcher

- The Dark Knight

- The Game

- The Morning Quicky

- Tiffany Taylor

- Tiger Woods

- Tila Tequila

- Tobey Maguire

- Tom Arnold

- Tom Brady

- Tom Cruise

- Tom Hanks

- Tommy Lee Jones

- Tony parker

- Tori Spelling

- Travis Barker

- Tricia Helfer

- Tyler Perry

- Tyra Banks

- Uffie

- Uma Thurman

- Usher

- Vanessa Hudgens

- Vanessa Marcil

- Vanessa Minnillo

- Victoria Beckham

- Victoria Justice

- Victoria Silvstedt

- Vida Guerra

- Vin Diesel

- Vince Vaughn

- Virginia Tech

- Website News

- Weird Al

- Wesley Snipes

- Whitney Houston

- whitney Port

- Whoopi Goldberg

- Will Ferrell

- Willem Defoe

- Wilmer Valderrama

- Winona Ryder

- Woody Harrelson

- Woody Harrison

- Yesica Toscanni

- YouTube

- Yukie Kawamura

- Zac Efron

- Zachery Ty Bryan

- Zooey Deschane

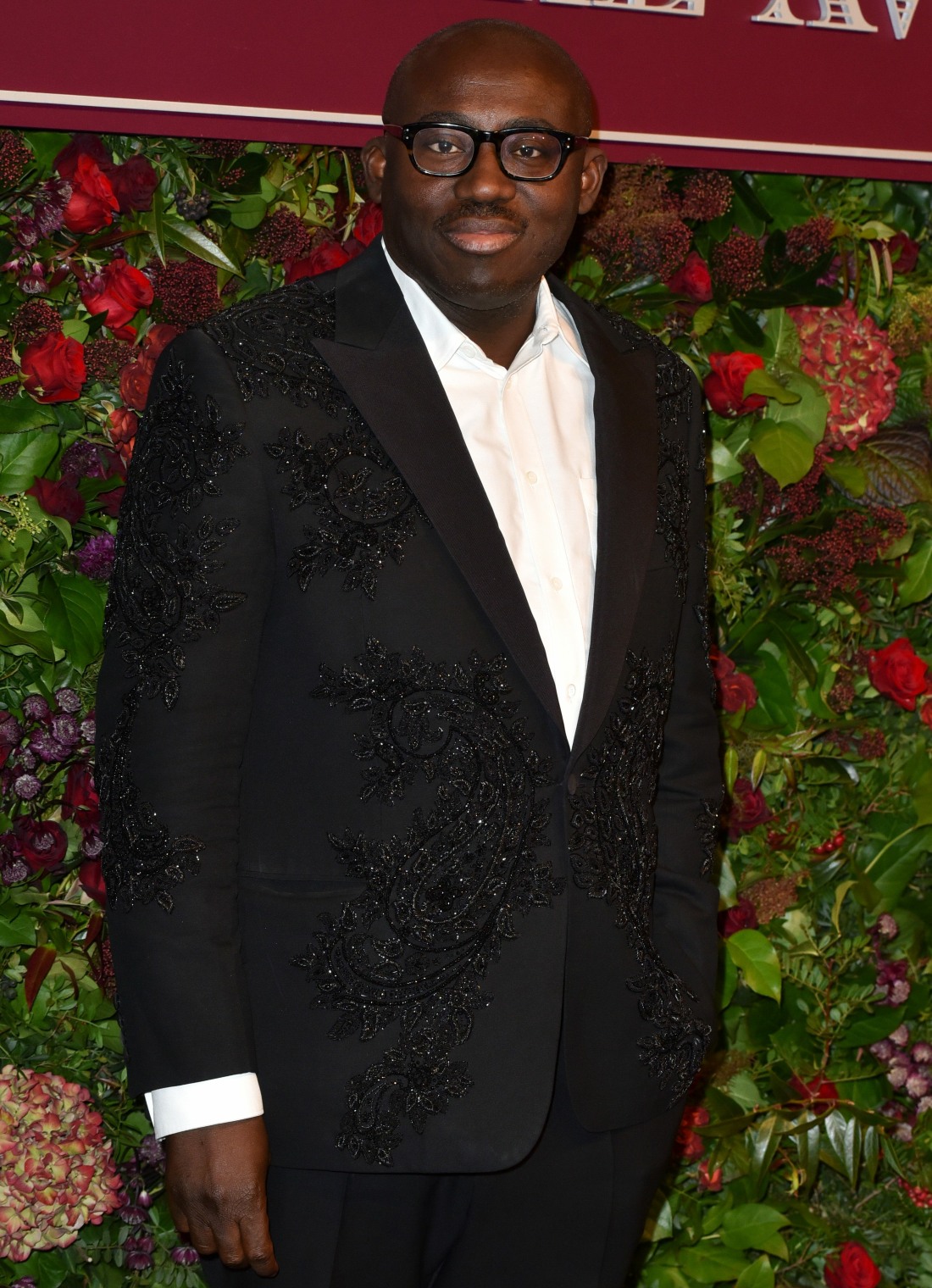

Was Edward Enninful pushed out of British Vogue because he was too ‘woke’?

Author: | Filed under: CelebritiesThere are seemingly many layers to Edward Enninful’s ousting at British Vogue. Enninful handed in his resignation last Friday, saying that he was stepping into a global advisory role for international Vogue editions. Within hours, the rumors began that Enninful had gone up against Anna Wintour and she destroyed him. While I don’t doubt that some version of that actually happened, I also think there was probably a lot more nuance to this entire situation, including the fact that Enninful can and will make a lot more money outside of Conde Nast. The Telegraph had a surprisingly nuanced piece about how a behind-the-scenes ideological battle was part of this Enninful-vs-Wintour issue too. Unfortunately, the piece is called “Why Anna Wintour won Vogue’s war on woke.” The actual analysis is actually spot-on though. Some highlights:

Enninful clashed with Roger Lynch, the CEO of Condé Nast: According to some reports, Enninful’s decision was made at least in part because of a clash of ideas, with Lynch concerned about his progressive politics. At heart, Vogue is just another business, and as recent incidents at Nike, Bud Light, Disney and countless others have shown, the corporate world is an increasingly fraught place where you must strike a balance between selling your product and being seen to hold the “right” views.

Enninful’s progressive politics: As well as immaculate fashion chops (he started out as a stylist), Enninful had a contacts book bulging with famous friends. In the years since, he has cemented a reputation for diversity and activism. He featured the first trans contributor, Paris Lees, and cover star, Laverne Cox. Recent covers have featured disabled subjects. Last September he even featured a man, Timothee Chalamet, alone on the cover.

Advertisers loved Enninful: Advertisers were reportedly keen on Enninful’s new direction, which gave them the chance to be adjacent to a diverse, inclusive range of talent with right-on, social-media friendly messaging. It attracted hundreds of millions of pounds in advertising from companies like BMW. There were positive noises about circulation, too. Condé Nast can be opaque about its numbers, but Enninful’s Forces for Change issue in September 2019, which was guest-edited by the Duchess of Sussex and had Greta Thunberg on the cover, sold out in days.

But British Vogue became joyless: For others, however, Enninful’s activism came at the price of an entertaining magazine. “Everything that made [Enninful] not a classical editor (that is to say, a trained journalist with a ‘words’ background) was why he flew so high early on,” wrote Farrah Storr, former editor of Elle, in a Substack post. “Vogue morphed from a playful, albeit slightly horsey, fashion magazine into a deeply political manifesto.” Along the way, she writes, people stopped buying it: instead it was given away or sold at a discount. “It was joyless, too political and seemed to have forgotten its role as a high-end shopping magazine.”

A larger issue for businesses: “It’s pivotal for businesses to have diversity, not only for the moral sense but the business sense, too” says Octavius Black, the chief executive of consultancy MindGym. Black co-founded his management consultancy with a psychologist, so knows a thing or two about behavioural science. “We know that companies that are inclusive outperform those that are not. But some of these issues can become polarising, as it looks like certain protected categories compete with each other. Women’s rights and trans rights can come into conflict, as we’ve seen in Scotland. The risk is you’re appealing to a niche group and end up reducing your appeal to others. You want to be selling why your products are brilliant, and how you as a company are behaving responsibly and ethically in pursuit of that, but not taking a position on divisive social justice issues. You’d be unwise in America coming out for – or against – abortion, for example, which is not to say that it doesn’t matter, but it’s not the role of a company to take a position on those things.”

Vogue’s readership: Progressive views on gender might help win over celebrities, publicists and advertisers keen to bask in a bit of reflected diversity on social media, but they do not necessarily play as well with the core readership. Vogue readers skew older and female, while readers in the new territories into which Condé Nast is keen to expand: such as the Middle East, India and China, may have more traditional views on social matters. The Enninful approach seems to have been deemed too great a risk.

“You’d be unwise in America coming out for – or against – abortion, for example” – Wintour is a pro-choice Democrat and Vogue has, historically, editorially supported reproductive choice, abortion and birth control. But I get the larger point, which is: Enninful’s tenure at British Vogue was notable for how progressive and inclusive he made the magazine, but it came at the cost of alienating the core readership. Which I agree with, actually – you can argue that Enninful brought new readers, younger readers to the magazine, but if your core readership of middle-aged (white) women are canceling their subscriptions, what is the real cost-benefit analysis? Can you “make up” those lost readers in new readers, readers from a younger generation which doesn’t believe in buying fashion magazines at a newsstand, a younger gen which has already seen the new collections on social media? Is the purpose of British Vogue to give readers what they want or what they need? It’s not a woke-vs-non-woke thing, it’s about the changing landscape of print media.

All that being said, for all of the crying about “wokeism,” Enninful was overwhelmingly a political traditionalist who sucked up to the white establishment in the UK.

Leave a reply